The Digital Doctor: How Technologies Enhance Health Care

Published by Healio Gastroenterology.

While physicians as a whole slowly adopt new technology, such as implementation of electronic medical records, a new wave of clinicians look toward clinical research and doctor involvement to bring digital technologies into the GI practice to help clinicians improve patients’ experiences, sources told Healio Gastroenterology.

“Medical school curriculums and house officer training programs will need to adapt along with the technology to provide training. It will also be very important for physicians to become innovators and entrepreneurs,” William D. Chey, MD, professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan Health System, division of gastroenterology, Ann Arbor, Mich., told Healio Gastroenterology in an interview. “In my mind, that is the only way that the system will evolve in a way that serves the primary end users — patients and health care providers. This is quite different from the current focus of health information technology — the electronic medical record, which has been developed primarily to satisfy regulatory obligations and to maximize billing.”

“If you talk to a lot of physicians, they see many aspects of the current generation’s electronic medical records as an impediment rather than a help,” Chey said at a press briefing during the ACG 2015 Annual Scientific meeting held in Hawaii, referring to mobile health applications or ‘apps.’

Up to this point, electronic health technologies have been developed without the insight of physicians, Chey explained. “Doctors have to become increasingly involved in the development of these e-solutions and apps,” Chey said.

Adapting to Change

With current movements in health care changing how doctors are paid and how patients are managed, experts discussed an impending increase in the use of digital health technologies within the next few years.

“The health care system is starting to look more and more like managed care,” explained Brennan M. Spiegel, MD, MSHS, AGAF, FACG, director of health services research in academic affairs and clinical transformation at Cedars-Sinai Health System.

“We get paid a certain amount to take care of a patient. So, our goal now is to actually keep people out of the hospital, away from the doctor and away from the emergency department, because that is really expensive,” Spiegel said in an interview with Healio Gastroenterology. “We need to move health care away from the physical buildings of hospitals and offices and into everyday life where people live, work and play.”

Gastroenterology is often considered a field that is already driven by technology.

“It is clear that medicine as a profession is rapidly changing. GI in particular is a technology-driven field. We have all grown accustomed to the benefits of technology in terms of visceral and luminal imaging as well as the assessment of function as it pertains to GI disease,” Chey said. “Digital platforms will soon allow us to assess and track symptoms and diet in ways that will change the dynamic between patients and health care providers.”

Patient-Physician Communication

The use of a variety of technologies, such as wearable biosensors, apps, social media, conferencing and telemedicine, will allow health care providers to monitor and manage populations in real time, Spiegel explained.

“For GI, using technology to reach out to patients is a new technique to take care of our chronically ill patients, such as patients with inflammatory bowel disease or irritable bowel syndrome or any number of other conditions like celiac disease,” Spiegel said. “We can monitor how patients are feeling throughout the day and throughout the week. We can use this information to make decisions to keep people healthy rather than having to have them come in to the hospital.”

“Biosensors will further enhance the ability of health care providers to understand a patient’s illness experience, the impact of GI problems on their quality of life and ability to function, and effectiveness of any interventions offered. These platforms will amplify the ability of health care providers to provide easy-to-understand, medically responsible education and recommend evidence-based treatment plans in an efficient and convenient manner,” Chey said. “With all of this data freely flowing between patients and their health care providers, it is clear that we will need the hardware, software and training to make it mutually beneficial vs. an exercise in futility.”

Spiegel believes there is a new physician emerging — the digitalist — who will incorporate such technologies in the GI practice for the benefit of both the health care provider’s practice and the patient. Along with physicians specializing in digital communication, apps that undergo clinical testing before use, as well as follow-up quality testing, may allow them to play a larger role in the management of chronically ill patients with GI diseases and syndromes.

The Digitalist Concept

According to Spiegel and Chey, a digitalist is a type of health care provider using digital technologies to reach out from a central location to physicians and patients. The digital technologies used — including wearable biosensors, mobile health apps, social media, telemedicine and others — would focus on patient-physician communication outside the traditional in-office provider visit.

“This doctor doesn’t quite exist yet,” Spiegel said. “It is starting to form, and I predict that within 3 to 5 years, we will be hearing about digitalists, or doctors like digitalists, much more frequently,” Spiegel told Healio Gastroenterology.

“At a training level in medical school, there should be career pathways that focus on technology,” Chey also said in Hawaii.

“It is not clear whether every doctor will be a digitalist or if there will be dedicated doctors who focus primarily in this capacity. Time will tell,” Chey told Healio Gastroenterology.

Spiegel is also the director of a group at Cedars-Sinai called Cedars-Sinai Center for Outcomes Research and Education (CS-CORE). “In addition to its focus on traditional health services research techniques, the Center is also developing new technological innovations to expand care outside of the provider visit, including use of patient-provider electronic portals to support clinical decision making in electronic health records,” according to the CS-CORE website.

“I am a budding digitalist. We are testing new ways and new models for monitoring and taking care of patients. The reality is that it is going to be a lot of time before this vision is real. You still have to do things the old fashioned way, but we are looking at new techniques,” Spiegel said. “We are looking at telehealth. We are going to start a study in the next 6 months where we will see if we can remove patients from our clinic and just take care of them by remote communication — video conferencing enhanced with computerized histories. We are going to start a study to see if we can replace our clinic completely with telecommunication. We are using biosensors to monitor people and it is still really in the research capacity. So, I am a digitalist, but still in the research phase.”

Spiegel said new technologies will not replace the work of the health care provider.

“We need doctors more than ever because the technology is allowing the doctor to do what they do best, which is to be a human being and look at another human being and understand what is happening in his or her life. We need doctors to look at the patient’s eyes and look at the patient’s body and understand nonverbal cues. Computers can’t do that and never will,” Spiegel said.

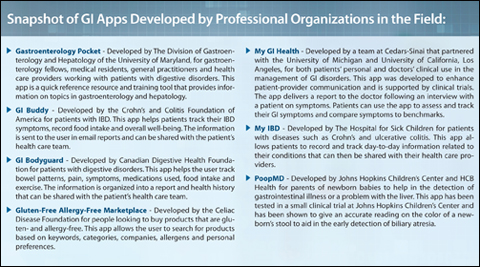

Digital Health Apps in GI

Many challenges exist in the development of an app that adds value to both the patient and health care provider. Thousands of health-related apps exist — currently more than 100,000 some estimates say — but few have been tested to verify any advertised benefits.

Spiegel shared an anecdotal example from hepatology that stresses the importance of clinical research in the development and testing of apps.

“There is an app that has been studied quite carefully,” Spiegel said. “It is the EncephalApp, an app for measuring encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis. The reason it is so important is because encephalopathy can be difficult for some people to diagnose. And the issue is that if someone is encephalopathic, they can get into their car and crash it into other people and you would never have even realized that they shouldn’t have been driving.”

Studies have shown that this app can diagnose the problem, Spiegel explained.

In a study published recently in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, researchers concluded: “A smartphone app called EncephalApp has good face validity, test-retest reliability, and external validity for the diagnosis of covert hepatic encephalopathy.”

Another app that has become available and clinically tested is My GI Health, which was developed by Spiegel and colleagues at Cedars-Sinai.

My GI Health is an app that interviews users about GI symptoms and delivers a report to the doctor. Patients can use the app to assess and track their GI symptoms. The app also helps the patient compare symptoms to benchmarks and learn more about any symptoms they experience.

“What we have been trying to do with My GI Health is to give the patient and the doctor a more efficient, productive and positive experience in the clinic,” Spiegel explained. “The doctors that we work with have been very positive about the capability of the app, particularly its ability to take a history for us and document it. That saves doctors time and it allows them to do what they do best, which is to just sit down and talk with people — person to person.”

Yet, the ability of a computer algorithm to take patient history has been shown to excel compared to a health care provider’s ability to do the same task in clinical trials, and the same has been shown with the My GI Health app, which took 4 years to develop, Spiegel said.

“We put a lot of research into it. There are very few apps, still to this day, that are supported by any actual research.”

A study performed by Christopher V. Almario, MD, division of gastroenterology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, and colleagues showed that history of present illness reports were of higher quality overall when generated by a computer compared with history of present illness patient reports written by physicians during usual care visits in a clinic. The researchers, who published the report in the American Journal of Gastroenterology, also said the computer-generated reports were better organized, more succinct, more comprehensible, more complete and more useful.

Although the computer outperformed the health care providers in collecting data, the researchers remind everyone: “These results do not indicate that computers could ever replace health care providers. The art of medicine requires that physicians connect with and empower patients, interpret complex and oftentimes confusing data, render diagnoses despite imperfect information and communicate in an effective manner. Nonetheless, this study suggests that computers can at least lift some burden by collecting and organizing data to help clinicians focus on what they do best — practicing the distinctly human art of medicine.”

Response from Peers, Patients

There is “a mixture of excitement, fear and skepticism” when discussing the technology revolution with physician peers, Chey said. “Most gastroenterologists embrace the notion that technology can transform the way we care for patients. Certainly, endoscopy has done just that. However, many gastroenterologists are quite jaded after largely negative experiences with the current generation of electronic medical records. When confronted with the fear and skepticism, I try to point out that adoption of health information technology into our practices will be an iterative process — a process that we are just at the start of. I firmly believe that as the focus moves from regulatory issues and billing to the relationship between patient and health care provider and improving care, things will significantly improve.”

When it comes to patients, the digital divide still plays a big role.

“The idea that, in general, older people are less inclined to use technology than younger people makes sense,” Spiegel said. “We use My GI Health in our clinic. And we invite everyone to use the app to prepare for the visit. And then it is up to them.”

“We basically tell our patients to help us help you by filling out the questionnaire online and help us get a head start to see what the goals are for the visit and what your story is. But, if you don’t want to do it, that’s fine. Either way we are still going to see you and learn about you. And some people do it and some people don’t,” he added. – by Suzanne Reist

References:

- Almario CV. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;doi:10.1038/ajg.2014.356.

- Bajaj JS. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2014.05.011.

Spiegel BMR. How Information Technology Will Transform Gastroenterology. Presented at: ACG; Oct. 16-21, 2015; Honolulu.

For more information:

- William D. Chey, MD, can be reached at University of Michigan Health System, Division of Gastroenterology, Taubman Center, Floor 3, Reception D, 1500 E. Medical Center Drive, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109; email: wchey@umich.edu.

- Brennan M. Spiegel, MD, MSHS, AGAF, FACG, can be reached at Cedars-Sinai Health System, Clinical Office, 8723 W. Alden Drive, Steven Spielberg Building, Los Angeles, CA, 90048; email: Brennan.Spiegel@cshs.org.

Disclosures: Chey reports he is a principal in My Total Health. Spiegel reports receiving research grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Nestlé Health Science, Shire and Takeda; serving as an advisor for Allergan, Commonwealth Labs, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Takeda and Valeant; and holding royalties, patents or ownership interest in AbStats, My GI Health and My Total Health.